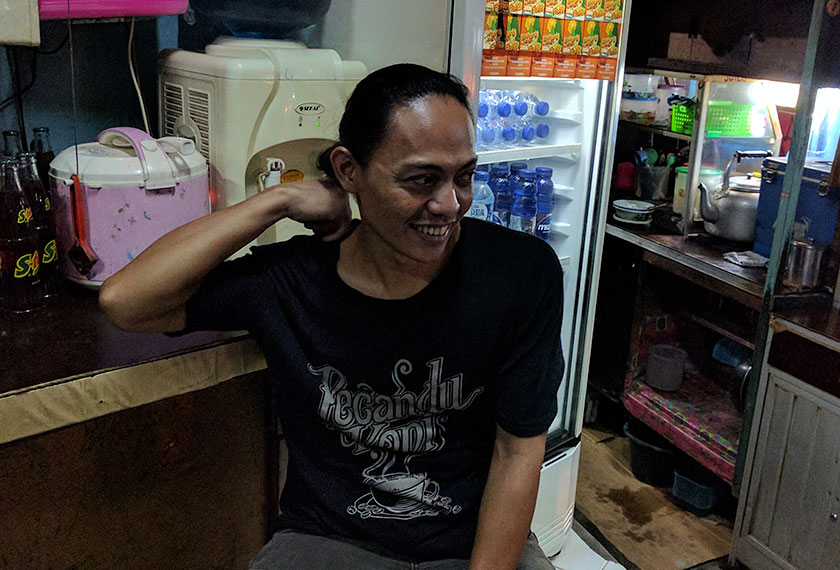

Pak Udin speaks in between serving patrons, many of whom just pop in for takeaway.

Despite having lived in Jakarta for most of his adult life, his spoken Indonesian is heavily accented with the plangent tones of a Javanese background.

"At the same time," he continues, "The city administration is more straightforward and organized. It's not just that things are cleaner, it's also the police, the fire brigade and other government services – they've all improved! You don't have to pay the Ketua RT (a local official) to sign forms.”

"In the past it was all about money. But now if you see rubbish or something wrong, you just take a photograph and send it through an online App called QLUE and they'll respond. Plus the complainant's name and number aren't revealed either."

There’s some truth to this. Tanah Abang an area once known for its gangs and lawlessness has undergone a clean-up.

The roads are no longer crammed with illegal street-vendors and the famous wholesale textile market is far more accessible than ever before.

Now, thirty-four year-old Pak Udin has witnessed the steady transformation of this densely-populated (at 31,000 people per square kilometre) and predominantly Muslim neighbourhood under the aegis of the hard-talking (some would say foul-mouthed) Governor, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama or Ahok.

Pak Udin and his wife Ibu Sri Yani are particularly impressed by the Kartu Jakarta Pintar, an ATM card-like facility that provides parents (generally the mother) with a stipend to use on a child's expenses, with the bimonthly funds ranging from IDR150,000—350,000.

"Everything you buy with the card must be for the child. You have to keep the receipts and hand them over to the teacher."

In a country with a notorious reputation for corruption, both young parents are clearly in awe at the professionalism of the scheme.

Still, I am a little surprised at their enthusiasm for Ahok given the overwhelming coverage of the blasphemy allegations against him.

I ask them whether they, as Muslims, haven't been turned-off the combative ethnic Chinese and Christian Governor.

"We are discussing the leader of an administration, not religion," Pak Udin explains, "This is about electing a Governor and an administrator, not a religious teacher. We must assess how well each of the three candidates performs and their programs.”

"Ahok gets things done. Automatically, those below him also get things done. With Ahok, we've seen him in action and experienced the results."

Surprised by his steadfastness, I probe further: "Don't you think he blasphemed?"

"I have watched the video and I don't think so. The people who are demonstrating have all sorts of different intentions. Not everyone wants Ahok locked up. Many of my neighbours from Tanah Abang tagged along to the demonstration on 4 November. They were just curious. In the event most were back by 3:00 PM.”

"Because I'm here all the time I listen a lot. We get all sorts of people at the warung – those who like Ahok, those who don't like him, supporters of Agus Yudhoyono and Anies Baswedan. During the 2014 Presidential Elections, this area was strongly for Prabowo."

The Javanese (at 36.2% of the population) are by far the largest ethnic group in the ten million-strong Indonesian capital, outnumbering the once-dominant local Betawi community.

Their perceptions of Ahok, his track record and the blasphemy case could well be the critical factor in the upcoming Jakarta polls.

Understated and often hard to “read”, it would be unwise to presume that they necessarily share the views of those who are demanding Ahok's immediate detention.

So, as Jakartans brace themselves for Friday's demonstration, it's important to remember that the city is less monochrome and infinitely more diverse than the gleaming white apparel worn by the supporters of the Front Pembela Islam (Islamic Defenders Front, FPI) and the National Movement to Safeguard the Indonesian Ulema Council’s Fatwa (GNPF-MUI), many of whom don't actually live in the city.

As Pak Udin said just before we parted, "This isn't a nation of just one religion, it's a nation of many religions."